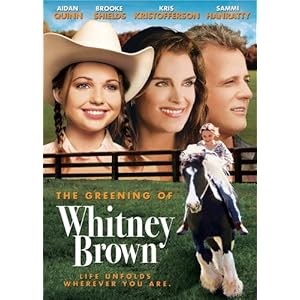

The biggest problem, according to my daughter, is that the story is "just like Cars." What does she mean? The story features a protagonist who is by all accounts a winner--competent, worshiped, healthy, wealthy. But he/she is simultaneously arrogant, impatient, unkind, boastful, rude. All the things that St. Paul in I Corinthians 13 says that love is NOT.

The biggest problem, according to my daughter, is that the story is "just like Cars." What does she mean? The story features a protagonist who is by all accounts a winner--competent, worshiped, healthy, wealthy. But he/she is simultaneously arrogant, impatient, unkind, boastful, rude. All the things that St. Paul in I Corinthians 13 says that love is NOT.Both of these stories are based on the Greek tragedy plot, in which a hero full of hubris (false pride) suffers for it and is humbled, which leads to deep personal change, or to death if he refuses to change.

The tricky thing is, a certain segment of the audience will not connect with a Greek tragic hero. Their sense of a good story is shaped by the Judeo-Christian plot of the Messianic hero, figured in Moses and David, Jesus and Peter. These guys come from humble beginnings, get kicked around a lot, sacrifice for others and in the end are exalted.

What does this mean for your writing? Be aware that getting your audience to connect with a hero who's arrogant and must get his comeuppance is extremely hard to pull off in certain genres. The only YA I've read that does this really well is Before I Fall by Lauren Oliver. You'd do well to study how she achieves an unlikable queen bee's metamorphosis into a humble and heroic figure.

I think the key to Oliver's success is that she sows seeds of hope for change into the characterization from the beginning. Neither Lightning McQueen nor Whitney Brown show any signs of having an identity apart from arrogantly putting others down. You want them to fail, and it's hard to hang onto audience when they wish nothing but bad for your protagonist.

Ramble news

Today, I'm over at Play off the Page, where Mary Aalgaard interviewed me about inspirations for Never Gone and why I mixed ghosts and God in the story.

Do you prefer to read about Greek tragic heroes or Messianic heroes? Can you think of other Greek tragic hero plots that worked well?

Interesting discussion. I really liked Cars, but I haven't seen the Greening of Whitney Brown.

ReplyDeleteI don't think I have a preference for my hero, but rather a preference that whatever the hero-type, it is done well. And A Christmas Carol is a Greek Tragic hero plot that worked exceedingly well, no? :)

Excellent example of old Ebenezer. We watch him with horror and fascination, hoping he will change.

DeleteI like both kinds of heroes!

ReplyDeleteI wonder if that's something that changes over time. My daughter is squarely in the period of wanting to closely identify with protagonists.

DeleteI wonder if you could argue that Pride and Prejudice is a little of both--Lizzy is the humble one who's exalted and Mr. Darcy is the exalted one who's humbled. Though, some of his "exaltedness" isn't real, only Lizzy's impression.

ReplyDeleteInteresting observation. It does seem like they both undergo transformations having to do with the issue of pride.

DeleteI was also impressed with Before I Fall and Oliver's ability to do that- it's an important study, I think. I'm a bigger fan of Messianic heroes, but I do feel they are bit overdone in literature for young people. Most MC's are the misfit/underdog. Maybe that's why I enjoyed Before I Fall so much. Hmm, I 'm going to think more about these Greek heroes and where they appear in the books I read.

ReplyDeleteI was thinking that too--about how underdog, Messianic heroes ARE overdone in kid lit, to the point it is moving from trope to cliche. Oliver gives a great model of how other writers might give us more Greek-style heroes just for variety.

DeleteI don't have a preference as long at they are done well.

ReplyDeleteI agree. Messianic heroes can be done poorly, too. In some MG and YA it's the kid who's too extremely down and out, with no allies at all. All characters (even villains) must some redeeming qualities, or other around them who see something good, in order to not seem like they're one-dimensional.

DeleteI'm going to add a third option to the mix- What about the anti-hero?

ReplyDeleteFrom what I know of anti-heroes, they rarely follow a standard hero plot, or if they do, it is to deconstruct the notion of heroism. The TV tropes site has some interesting tidbits about this kind of character. Cameron in Libba Bray's Going Bovine is a good example. He is of course modeled after Don Quixote by Cervantes, the model anti-hero.

DeleteThere has to be something that I like about the hero, at least by the end. It is satisfying to watch or read about someone who has learned to be humble and how to connect. It isn't very realistic, though. Most people don't change from hard-hearted arogance to generous spirits. Although, I did like the movie "Family Man" starring Nicholas Cage. He's self-serving at the beginning of the movie, but we later learn that he wasn't always like that.

ReplyDeleteI think the reason the change in Family Man is believable is because we see roots of another way in the character's history, just like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol.

DeleteSo that's a good technique to keep in mind when writing a Greek tragic hero sort of character--show that they weren't always so proud.

Looks like we've had many visitors at Play off the Page today. People like reading about where authors get their inspiration. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteThat's great news. Some of my Rabble Writers friends helped me spread the word via Twitter. You've been a wonderful host. Thanks again for interviewing me!

DeleteThe other thing about If I Fall is that you don't realize how mean the mc is at the beginning. It becomes clearer as she changes for the better just how much of a b**** she really was at the beginning.

ReplyDeleteI had an uneasy feeling about Sam in the beginning, but she was less witchy than some of her friends. That's another good technique--add a more arrogant, more flawed friend who makes the Greek tragic hero seem more redeemable.

DeleteReally, really good points. It's so hard to have a protagonist be an unlikeable character. There has to be some kind hint of possible redemption, I think. And even then, it's tough. Well said, Laurel. The Cars comparison was brilliant.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Carol. My daughter uses Cars as her quintessential example of an unlikable protagonist. It's been fun talking about literary history and tropes with her using animated films.

DeleteI like both types of hero stories, actually. And I agree, it's hard to get sympathy for an unlikeable character. Such a challenge!

ReplyDeleteSidenote: I, too, wrote about ghosts and God in the same story - sounds like I keep great company! :)

I thought Janet's Scrooge example was a good one. It's having those seeds of hope for redeemability that seems key for making the Greek tragic hero work. In Scrooge's case, it was learning about his past wounds that make you wish him well.

DeleteCool that you also write about ghosts and God.